Edouard Manet

For decades, economists, labor activists and researchers have lobbied for the four-day workweek. Companies are now beginning to listen.

How about a four-hour workday?

For years, I’ve been reading interviews with authors, full-time authors chiefly — who have described that or thereabouts as their limit.

That’s why I so much enjoyed “Darwin Was a Slacker and You Should Be Too, a fascinating article in “The Nautilus” which dissects the work habits of successful scientists, musicians, and authors.

While their workdays were short, writer Alex Soojung-Kim Pang found, their achievements were huge.

“Figures as different as Charles Dickens, Henri Poincaré, and Ingmar Bergman, working in disparate fields in different times, all shared a passion for their work, a terrific ambition to succeed, and an almost superhuman capacity to focus.”

Yet when you look closely at their daily lives, they spent only a few hours a day doing what we would recognize as their most important work.

The rest of the time, they were hiking mountains, taking naps, going on walks with friends, or just sitting and thinking.

Their creativity and productivity, in other words, were not the result of endless hours of toil. Their towering creative achievements resulted from modest “working” hours.”

Pang clocked their workdays:

Egyptian novelist Naguib Mahfouz, who wrote more than 30 novels: 4 p.m. to 7 p.m., put in after his day job as a civil servant. He took Fridays off.

Stephen King, more than forty novels, most best-sellers: a thousand words a day, in the morning. More than that is a “strenuous day.”

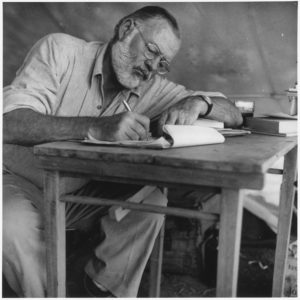

Some writers stretched their workday, but not by much. Ernest Hemingway put in six hours as did Gabriel García Márquez. But among these literary luminaries, the eight-hour day was absent; three to four hours seemed to be the average.

These writers weren’t lazy. They understood their limits, either instinctively or through experience, and knew that by working longer days they risked burnout, a creativity killer.

Clearly, this approach isn’t going to work in many fields. Can you imagine a newspaper reporter telling his editor, “Boss, I’m only going work four hours a day from now on?” Or telling your department chair you’re going to do the same? You’ll probably be shown the door. Consider showing them this article which is adapted from Pang’s book, “REST: Why You Get More Done When You Work Less.” The piece shows that brief daily sessions, focused with deliberate attention will improve your chances of success.

Let’s face it. We waste a lot of time during the day: chatting (gossiping) with colleagues, procrastination. Subtract all that and the workday sounds like those of successful writers and musicians.

Pang gets support from Robert Boice, a psychologist, who prescribed “brief daily sessions,” writing 10-60 minutes at a time, no more than 3-4 hours a day, followed by “comfort periods,” such as rest or other activities. This is the case even when writing is your “full-time” job.

The objective: to establish “regular work related to writing,” he wrote in the pricey cult classic “How Writers Journey to Comfort and Fluency: a Psychological Adventure,” which chronicles his work with blocked academics. “Be quick, but don’t hurry,” Boice said. “That is the secret to good writing.” His research found that binge writers produced far fewer pages than writers who followed his method.

Writing with full attention

Two factors determined the success of successful “slackers” profiled by Pang. They recognized the importance of rest to recharge their creative batteries and they were masters of time management. When it came time to work, they gave it their full attention. (Of course, as several commenters noted, they also had wives who took care of family and home responsibilities, freeing them to write and take long walks.)

Writing, like the mastery of a musical instrument, demands “deliberate practice,” Pang writes, “engaging with full concentration in a special activity to improve one’s performance.”

This is possible even if you have a full-time job and can devote only part of your day or week pursuing your writing dreams.

It may take longer to finish your projects this way, but if you burn yourself out with long work sessions, chances are strong you’ll quit anyway.

How well do you manage your time? Do you work with relentless focus or fritter the time away, stopping to surf the Web, or heading to the break room to learn the latest office gossip when you’re stumped?

Or when you’ve put in a productive stretch of work, do you decide to keep working or do you hit save, take a walk with the family, or read a good novel or essay just for the enjoyment of it?

Go ahead. You deserve it.