What is the most important lesson you’ve learned as a writer?

Do the work. That’s a variation on the familiar “ass in chair” exhortation, but it refers to much more than typing words on a screen. Mark Lett, my longtime boss at The Detroit News and later the executive editor of The State at Columbia, S.C., used the phrase often. “Do the work” means attending to all of the tasks—some more tedious than others—that lead to results. When I’m pursuing a non-fiction story in my day job as a feature writer for Bloomberg Businessweek magazine, doing the work means, for instance, looking at every page of notes, documents, and other materials I’ve gathered in my weeks of research, even though only about 1 percent of what’s there is likely to make it into my story. As a novelist, doing the work is more about sitting at my laptop every morning and putting words to digital paper. Whether it’s 300 or 500 or 1,000 words a day, if I keep doing the work, I know I’ll eventually have enough in front of me that I can begin to see my way to the middle of a book and, finally, an end. I’ve heard writers say, “That story just wrote itself.” If only.

What’s been the biggest surprise of your writing life?

That people would profess to love something I wrote. I still get a thrill when a reader posts an online comment or sends me an email saying they liked one of my pieces or books. At the other end of the spectrum, I’m still disappointed when people dislike something I’ve written (which happens much more with fiction than non-fiction). My favorite comment ever is probably an email I received from one Evan Vetere, a Wall Street Journal subscriber. I had written a Page One story about a World War II lieutenant and the Jewish boy he rescued from Dachau. Mr. Vetere wrote me: “Your profession exists so people like you can write stories like this.” I’ll never forget it

If you had to use a metaphor to describe yourself as a writer what would it be?

Although it’s not entirely accurate, the one that pops immediately to mind is tortoise. I’m not a particularly slow writer, and sometimes, especially on deadline, I can be pretty fast. On September 11, 2001, I took 30,000 words of WSJ staff memos and turned them into a 3,000-word front-page story in under three hours. But I am tortoise-deliberate. I have a process that revolves mostly around elimination. In my non-fiction day job, I pile interviews, observations, documents and other stuff into big piles of clay that I then whittle away, getting ridding of stuff until what remains is my story. Fiction is different insofar as I have a lot more material I can use—virtually everything I’ve ever seen, heard, smelled, tasted, overheard, read, imagined, etc. I start by choosing what to put on the page. As the words multiply and the characters come more clearly into focus, the story actually begins to narrow because as I’m choosing where it will go, I’m also choosing where it will not, and the farther it goes in one direction, the less likely it’s going to go in infinite others. Then, when I’m rewriting, I’m doing a lot more subtraction than addition. Unlike some writers I know, I love rewriting, especially the tactile feel of using a pen to strike out words, phrases, and sentences. Eventually, I know that if I do the work and stick to my laborious process, I will give myself the best chance to produce something that someone will tell me they love.

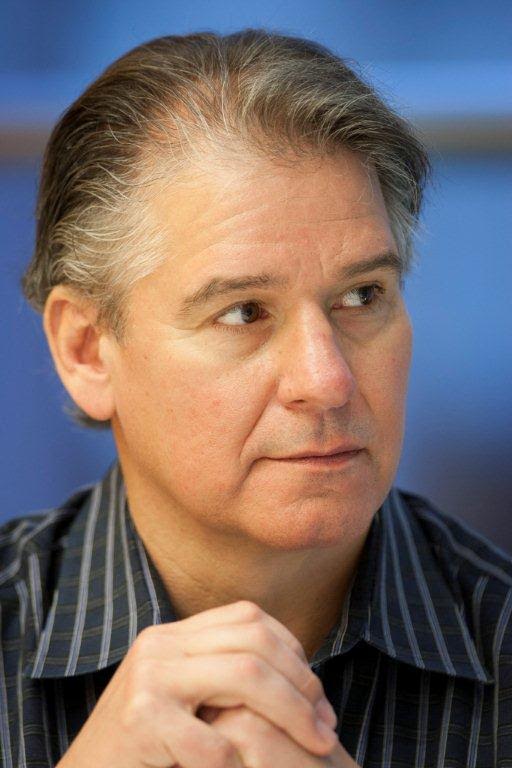

Bryan Gruley is the award-winning, critically acclaimed author of “Bleak Harbor,” which Gillian Flynn called “an electric bolt of suspense,” and his latest crime thriller, “Purgatory Bay,” which Michael Connelly says is “impossible to put down.” Gruley was nominated for an Edgar for his debut novel, “Starvation Lake,” the first in a trilogy set in a fictional northern Michigan town. When he’s not making things up, Gruley writes long-form features on a wide variety of topics as a staff writer for Bloomberg Businessweek magazine. He has won numerous prizes for his journalism, and shared in The Wall Street Journal’s Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the September 11 terrorist attacks. He lives in Chicago with his wife, Pam.