“Teach yourself to work in uncertainty.”

– Bernard Malamud

Month: January 2020

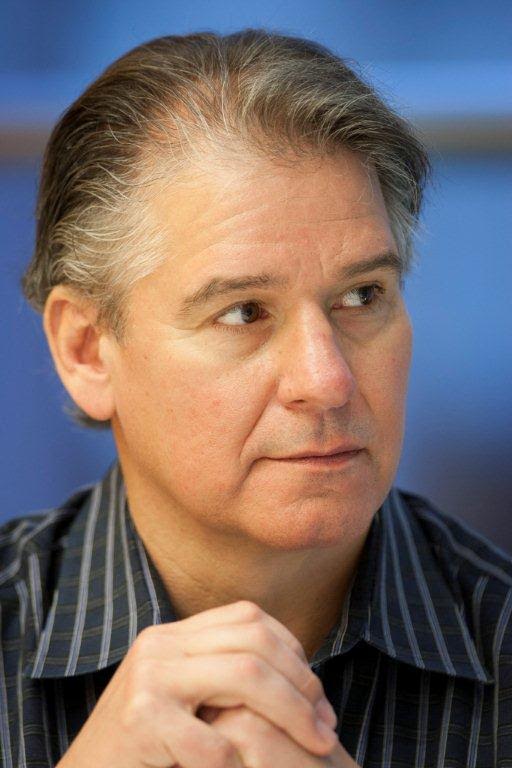

Switching from nonfiction to making things up: An Interview with Greg Borowski. Part One

Interviews

Every year for the past quarter-century, Greg Borowski, longtime watchdog editor at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, writes a short story keyed to the holiday. His offering this year was “The Christmas Boxes,” a poignant story about a woman who connects with her dying mother suffering from dementia when she opens a box of Christmas decorations, each with their own memory.

Writing fiction has profound implications for those trying to get better at narrative nonfiction. And vice versa.

That’s what I learned recently when I interviewed Borowski for Nieman Storyboard.

Narrative writers like Borowski, whose credits also include “First and Long: A Black School, a White School and Their Season of Dreams,” call on the same tools to produce the verisimiltude that their fiction counterparts strive for: details, scenes, dialogue, drama and suspense. But there is a crucial distinction.

Here’s an excerpt from our interview, reprinted with permission:

Your story has all the elements of narrative nonfiction. How do you manage to write a made up story that feels so real?

I tend to fall back on techniques I learned as a journalist: Use only telling details. Make every word count. Cut anything that does not advance the story. Don’t use quotes/dialogue as exposition. Less is more.

With these stories, I try to write cinematically. That is, I can see the scene in my head — where people are standing, what the room looks like, every nod, gesture, voice inflection. When people are told to write descriptively, it can come off like an inventory of a room. When they describe action, it can read like stage directions. My goal is to have the reader feel like the scene is happening in front of them — for them to experience the story, not just read the story.

Beyond that, I try to do double duty with descriptions.

For instance, in the first paragraphs of the story, I wanted to get across the idea Lauren is a busy professional woman in a tough spot at Christmastime without saying any of those words. Likewise, I felt like I had a single paragraph to describe both the house where she grew up and what it was like to grow up without a father around.

Even though it’s fiction, do you have to report it?

As a rule, yes. But the stories I write generally focus on relationships between people, and often carry some magical Santa-esque element.

Rather than reporting out scenes and locations, I think of this more in terms of making sure the stories hold together within themselves. That is, does the reality they create — even if it’s something fanciful or magical — ring true? As I work through the drafts, I try to scrub them with that in mind: Is the character consistent throughout the story? Do the ages and timelines fit together properly? My wife, Katy, who is usually the first person to read them, is a good check on this. So is Jim Higgins, an editor at the Journal Sentinel who coordinates getting them published in print and online each year.

When they raise questions of reality or continuity, I sometimes want to reply: “Come on. It’s fiction. Anything can happen in fiction.” But that’s lazy and untrue. Instead, their questions are a sign I need to go back and rework something.

You’re an investigative journalist. How is writing fiction the same and dramatically different from narrative journalism?

The parts that are the same are easy. You need subjects/characters that are well-developed, a structure that includes conflicts or obstacles, strong dialogue and a resolution that is satisfying and true to the story. In short, something has to happen in the story and everything that is included has to drive the reader to that conclusion. Additionally, both forms require a steady hand from the writer. You’re taking the reader along for a ride, so the reader has to feel comfortable — not that they won’t be saddened or joyful along the way, or that there won’t be any twists or turns. Just comfortable that you, the author, know where you are going and can get them there.

For me, a major difference is that with narrative nonfiction you’re often trying to take real life, the ordinary, and make it feel special or magical. In my Christmas stories, I’m trying to take the magical and make it seem ordinary. That is, grounding it in reality. For instance, in this year’s story, I knew I needed a few touchstone family decorations as a plot device. I knew one would be a snow globe because, well, my daughter has several that come out at Christmas time and it seemed to fit.

It wasn’t until I typed out what was inside the snow globe — a winter scene with a church — that the next line of dialogue popped into my head:“That’s our church. That’s where I got married.” It wasn’t until I put the snow globe into the mother’s hands and allowed her to shake it, that I realized it was a metaphor for things being jumbled and then settling. And, really, that’s the arc of the story itself.

What lessons can writers of narrative nonfiction draw from writing fiction?

I think there are lots of lessons to be drawn simply from trying something different.

A major lesson, though, is that to truly resonate with readers, a story has to operate on multiple levels. You need the strong characters and cliffhangers and twists to pull you along, but what’s the deeper thing the story is really about? Redemption. Forgiveness. Healing.

Once you settle on that, it should inform and shape the structure, plot and dialogue and everything else that goes into the piece.

Next week: Part Two

Craft Lesson: Excuses, excuses

Craft LessonsI’m too young to make it as a writer.

I’m too old.

Excuses, excuses. These two defenses cripple many writers from doing the work it takes to produce a novel, screenplay, a poem, a nonfiction book or article or an enterprise story.

I’ve heard—and made—them over the years. They keep writers from achieving many of their writing dreams which is a darn shame.

I’ve sat with writers who, with sincerity and some madness, make them. Here’s what I want to tell them:

Langston Hughes published his first major work when he was 19. Stephen King, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Gabriel Garcia Marquez were 20. 21: Bret Easton Ellis and Mary Shelley. 22: Margaret Atwood, Ray Bradbury. Worried you’re too young? Read the rest of this list.

James Michener wrote 40 books after he turned 40. Raymond Chandler was 43 years old when he published his first novel, “The Big Sleep.” Anna Sewell started writing “Black Beauty” when she was 51; she was 57 when she sold the book. Frank McCourt published his Pulitzer Prize-winning memoir, “Angela’s Ashes” when he was 66. Harriet Doer’s first novel, “Stones of Ibarra” won the National Book Award. It was published when she was 74. Worried you’re too old? Read the rest of this list.

Here’s another potent excuse, one fueled by what psychologists call the “Victim Mentality.”

I’m quitting because I was rejected. Do you think you’re the first?

“First, we must ask, does it have to be a whale?” That was the response of one of the multiple publishers who turned down Herman Melville’s “Moby Dick.” .

“An irresponsible holiday story that will never sell.” That was the rejection Kenneth Grahame received for his classic “The Wind in the Willows.”

“An endless nightmare. I think the verdict would be ‘Oh don’t read that horrid book.’” H.G. Wells got this rejection for “The War of the Worlds,” still in print more than a century after it was published.

Joseph Heller got 22 rejections for his satirical masterpiece “Catch-22.” One of them read, “I haven’t the foggiest idea about what the man is trying to say. Apparently the author intends it to be funny.” For more on famous authors and their rejections, read the rest of the list here.

There are lots of other excuses writers make. I’m too tired. My friends give me a hard time because I don’t have time for them. I’m not inspired. Revision means I’ve failed. I don’t have enough time.

Go ahead and use them. You’ll get nowhere fast.

But here’s what I’d rather say. Challenge them. You can make time. Mothers write during their baby’s nap time. When I was working demanding jobs, I got a lot done just by setting my alarm a half-hour early and writing. Scott Turow wrote the first of his best-selling thrillers, “Presumed Innocent,” on the train to his job as a federal prosecutor.

Good friends understand. Inspiration happens when you’re at your desk. And revision offers unlimited chances to make your writing better.

Excuses try to release a person from blame. When it comes to writing, as with many other endeavors, most of the time there’s no one to blame but yourself. It’s easy for me to say take responsibility, but what I’d rather say is you don’t need to make excuses. Do the work.

“Getting good as a writer, or any kind of storyteller, seems to me a lifelong pursuit,” says Jacqui Banaszynski, Pulitzer Prize-winning writer and editor of Nieman Storyboard which celebrates narrative nonfiction. “And one that demands we realize there is always another level to reach and dare ourselves to take some creative risks as we get there.”

Keep that counsel close. Dare yourself. And just bear in mind that if there’s anything the history of publishing demonstrates, it’s that writing success has no shelf life, and there’s no accounting for taste.

Barbara Tuchman on motion in prose

Writers Speak“I try for motion in every paragraph. I hate sentences that begin “There was a storm.” Instead, write “A storm burst.”

– Barbara Tuchman

Dialogue’s Roles in story

Writing TipsDialogue is the breath of every story. Use it to develop characters, advance the action, and pace your stories.

Six Questions to Drive Your Story’s Plot

Craft Lessons

There are two types of writers: plotters, who plan out their story, sometimes in great detail before they begin, and “pantsers,” who prefer to write without knowing the outcome in advance, content to sit at their desk and discover as they go along. I’m one of the latter.

But recently I pulled a book from my shelves that has led me to reconsider my approach. “Plot” is a 1988 primer by Ansen Dibell that takes a comprehensive look at this crucial element of storytelling.

“Ask someone what the plot of their favorite novel or story and they will tell you what happened in it. That’s useful shorthand when the conversation is about finished stories, but when it comes to writing one, it’s like saying “that a birthday cake is a large baked confection with frosting and candles,” Dibell says. ” It doesn’t tell you how to make one.”

“Plot,” says Dibell, “is built of significant events in a given story — significant because they have important consequences.” She gives two examples. Taking a shower isn’t a plot, nor is braiding your hair. Neither have any consequences. They are incidents.

But if it’s Janet Leigh stepping into the shower while homicidal maniac Tony Perkins waits to pounce in Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho,” or the mega-long braid that is going to let a prince climb up the tower where Rapunzel is being held by a witch, these mundane incidents are transformed into plots.

For two months, I’ve worked nearly every day on a novel. I’ve written scenes and dialogue — the foundations of dramatic narrative — and summary narrative that leaps across time and space. But until I read Dibell’s book and other sources that discuss plotting, I didn’t realize I may just have been spinning my wheels because I didn’t ask some critical questions before I started.

- Is there something at stake? Plotting is the way you show things matter.

- Have I identified a protagonist, the person, in writing coach Jack Hart’s words, “makes things happen”?

- Can I summarize my plot in a sentence, the shorter the better, even if it takes hundreds of pages to play out? Two more examples from Dibell. “A group of British schoolboys, attempting to survive after their plane crash lands on a tropical island, begins reverting to savagery. That’s the plot of William Golding’s “Lord of the Flies.” “The police chief of a New England vacation community, although terrified of the ocean, sets out to destroy a huge killer shark.” “Jaws.”

- Have I established the sequence of events “that occur when a sympathetic character encounters a complicating situation that he confronts and solves,” which is two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning narrative writer Jon Franklin’s definition of story.

- Have I identified plot points, “any development that sends the story spinning off in a new direction,’ in screenwriting teacher Robert McKee’s formulation? These will help me plan my story trajectory.

- Is my story going somewhere? Do I have an ending in sight, or at least in mind? Knowing your ending allows you to establish foreshadowing that can help build suspense and forge your story’s meaning.

Pantsing is fine for some writers, and has worked for me in the past, mostly with short stories when the journey is relatively short. But as the word count of my book rises, I realize I’m not sure where I’m going. And I don’t feel like spending a lot of time creating a spineless mass of prose that I may end up jettisoning or face a massive rewrite. With these questions in mind, I’ve decided to stop spinning and start thinking first, pansting less and plotting more. If you’re struggling with a story, you might want to do the same.

Simone de Beauvoir on a day without writing

Writers Speak“A day in which I don’t write leaves a taste of ashes.

Brief Daily Sessions: Tip of the week

UncategorizedWrte in brief daily sessions, no longer than 30 minutes each, for a total of two to three hours day to avoid burnout.

h/t Robert Boice

Doing the Work: Three Questions with Bryan Gruley

Interviews

What is the most important lesson you’ve learned as a writer?

Do the work. That’s a variation on the familiar “ass in chair” exhortation, but it refers to much more than typing words on a screen. Mark Lett, my longtime boss at The Detroit News and later the executive editor of The State at Columbia, S.C., used the phrase often. “Do the work” means attending to all of the tasks—some more tedious than others—that lead to results. When I’m pursuing a non-fiction story in my day job as a feature writer for Bloomberg Businessweek magazine, doing the work means, for instance, looking at every page of notes, documents, and other materials I’ve gathered in my weeks of research, even though only about 1 percent of what’s there is likely to make it into my story. As a novelist, doing the work is more about sitting at my laptop every morning and putting words to digital paper. Whether it’s 300 or 500 or 1,000 words a day, if I keep doing the work, I know I’ll eventually have enough in front of me that I can begin to see my way to the middle of a book and, finally, an end. I’ve heard writers say, “That story just wrote itself.” If only.

What’s been the biggest surprise of your writing life?

That people would profess to love something I wrote. I still get a thrill when a reader posts an online comment or sends me an email saying they liked one of my pieces or books. At the other end of the spectrum, I’m still disappointed when people dislike something I’ve written (which happens much more with fiction than non-fiction). My favorite comment ever is probably an email I received from one Evan Vetere, a Wall Street Journal subscriber. I had written a Page One story about a World War II lieutenant and the Jewish boy he rescued from Dachau. Mr. Vetere wrote me: “Your profession exists so people like you can write stories like this.” I’ll never forget it

If you had to use a metaphor to describe yourself as a writer what would it be?

Although it’s not entirely accurate, the one that pops immediately to mind is tortoise. I’m not a particularly slow writer, and sometimes, especially on deadline, I can be pretty fast. On September 11, 2001, I took 30,000 words of WSJ staff memos and turned them into a 3,000-word front-page story in under three hours. But I am tortoise-deliberate. I have a process that revolves mostly around elimination. In my non-fiction day job, I pile interviews, observations, documents and other stuff into big piles of clay that I then whittle away, getting ridding of stuff until what remains is my story. Fiction is different insofar as I have a lot more material I can use—virtually everything I’ve ever seen, heard, smelled, tasted, overheard, read, imagined, etc. I start by choosing what to put on the page. As the words multiply and the characters come more clearly into focus, the story actually begins to narrow because as I’m choosing where it will go, I’m also choosing where it will not, and the farther it goes in one direction, the less likely it’s going to go in infinite others. Then, when I’m rewriting, I’m doing a lot more subtraction than addition. Unlike some writers I know, I love rewriting, especially the tactile feel of using a pen to strike out words, phrases, and sentences. Eventually, I know that if I do the work and stick to my laborious process, I will give myself the best chance to produce something that someone will tell me they love.

Bryan Gruley is the award-winning, critically acclaimed author of “Bleak Harbor,” which Gillian Flynn called “an electric bolt of suspense,” and his latest crime thriller, “Purgatory Bay,” which Michael Connelly says is “impossible to put down.” Gruley was nominated for an Edgar for his debut novel, “Starvation Lake,” the first in a trilogy set in a fictional northern Michigan town. When he’s not making things up, Gruley writes long-form features on a wide variety of topics as a staff writer for Bloomberg Businessweek magazine. He has won numerous prizes for his journalism, and shared in The Wall Street Journal’s Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the September 11 terrorist attacks. He lives in Chicago with his wife, Pam.

CRAFT LESSON: Attitude is all

Uncategorized

When I think of the hundreds of writers I have coached over the years, the best ones impressed me with their intellect and creativity. But what stands out most are not these strengths, important as they may be. Instead, it’s their attitude that makes them special in my eyes.

“The attitude we choose is by far the most important choice we make every day.”

LOU HOLTZ

Three decades of working with writers have convinced me that attitude — a way of thinking that is reflected in a person’s behavior — matters more than talent.

Talent may open the door, but attitude gets you inside the room.

“Most people place an undue emphasis on talent. I don’t doubt that it exists, but talent is essentially a potential for something. The issue is really not talent as an independent element, but talent in relationship to will, desire and persistence. Talent without these things vanishes and even modest talent with those characteristics grows.”

MILTON GLASER

Writing is a craft. It relies on a set of skills: reporting and researching, writing and revision (and more revision), understanding of structure, and facility with language, syntax, and style. Mastery requires years of study, work and above all, patience. Malcolm Gladwell famously estimated that achieving mastery in many fields requires 10,000 hours of work. True or not, there’s no doubt that becoming a good writer takes an enormous expenditure of time and effort. And without the right attitude, the willingness to do that work, the chances of success are slim to none.

In a field where so much — success and rejection, for starters — is out of a writer’s hands, attitude is one thing we can control. We can decide whether to procrastinate or write every day, give up or commit to one more revision, try our hand at a different genre, or learn and learn from other writers rather than be consumed by jealousy about their achievements.

Inspired by the wisdom of acclaimed designer Milton Glaser, legendary coach Lou Holtz and David Maraniss, the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author, I found myself musing about the nature of attitude and its importance to writers seeking success, including myself. Here’s what I came up with. It’s a partial list; I hope you’ll add to it in the comment section.

- Attitude matters than more than, talent.

- Attitude makes the difference between giving up and sticking with a story.

- Attitude means making one more phone call, writing one more draft, burrowing into your draft one more time to refine and polish your story.

- Attitude means a collaborative relationship with editors rather than a toxic one.

- Attitude means submitting a story the same day someone rejects it.

- In the end, attitude is what makes the difference between failure and spectacular success

CRAFT QUERY: What does attitude mean to you?

May the writing go well.

Photograph by Jeff Sheldon courtesy of unsplash.com